Exhibitions

Friday 16 February 2024

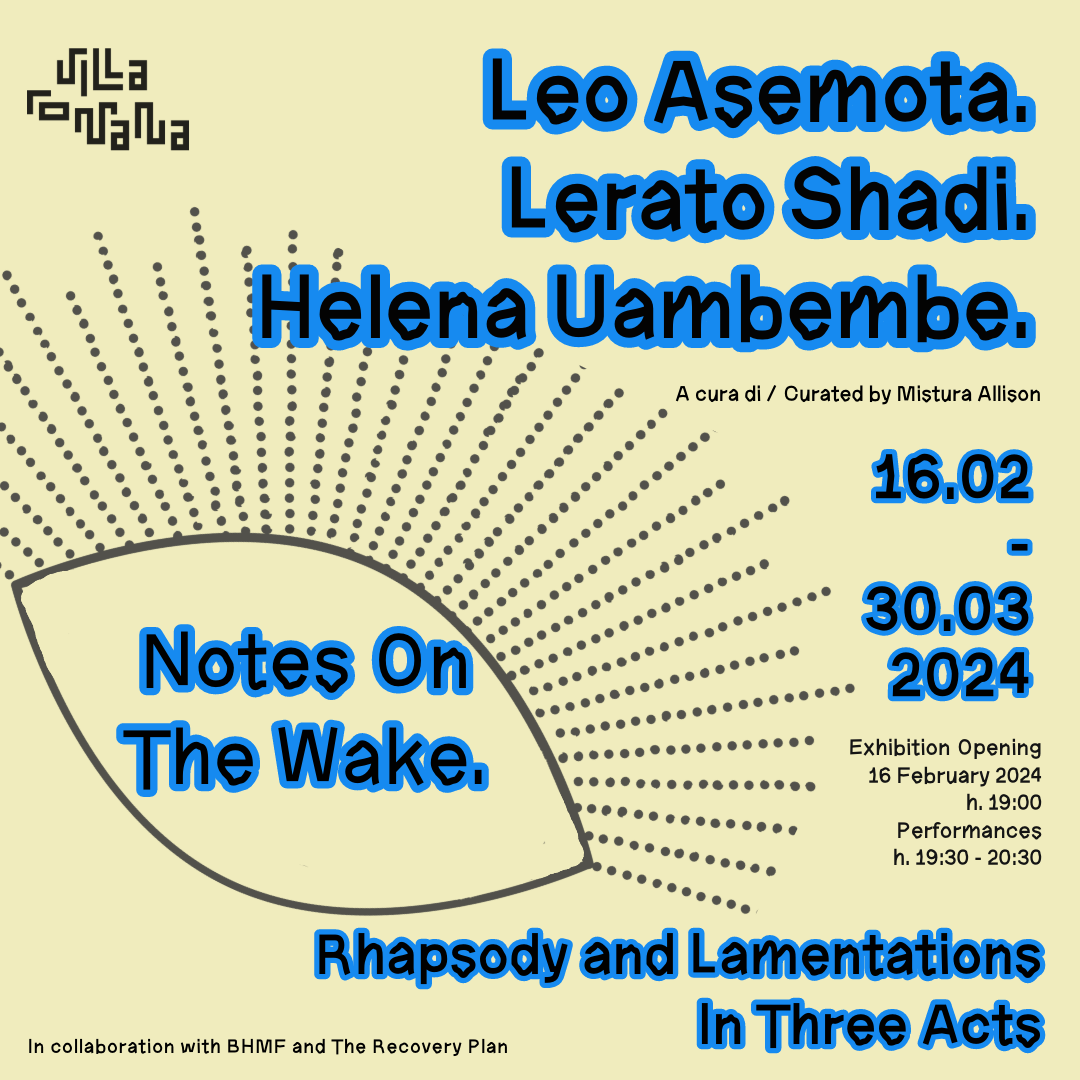

Notes On The Wake. Rhapsody and Lamentations in Three Acts

Exhibition

Vernissage,19:00 onwards

Performances, 19:30 - 20:30

Notes On The Wake. Rhapsody and Lamentations in Three Acts is a critical invitation to grieving and resting well in three acts, through the practices of Leo Asemota, Lerato Shadi and Helena Uambembe. The exhibition opens with performances and readings by Helena Uambembe, Naomi Kelechi Di Meo and Leo Asemota.

Curated by Mistura Allison, in the framework of Whole Rest, IX Edition by Black History Month Florence.

Notes on the Wake:

Rhapsody and Lamentations

in Three Acts

By Mistura Allison

Wake: grief, celebration, memory, and those among

the living who, through ritual, mourn their passing and celebrate their life in particular the watching of relatives and friends beside the body of the dead person from death to burial and the drinking, feasting, and other observances incidental to this.

In the wake, the past that is not past reappears, always, to rupture the present.

Christina Sharpe, In The Wake: On Blackness and Being (2016)

A silent hum.

In the quietude of contemplation, where the past and present converge, the exhibition unfolds like an elegy, a reflective homage to the intricate dance of memory, identity, and time within the African Diaspora. This exhibition and its contemplation navigate the waters of bearing witness, keeping watch, and mourning — each artist contributing a verse to this elegiac narrative.

Christina Sharpe's meditation on living "in the wake" offers a poignant framework for this reflection. "Wake work," as she delineates, is a practice of attending to the past's persistent echoes in our present lives, a form of resistance against the tide of forgetting. It is within this wake that we find Leo Asemota's Map of a City (2001), an intricate mapping of memory and witness through the urban landscape of London. Asemota's photographs within the booklet of witness appeal boards scattered throughout the city serve not merely as documentation but as a visual elegy to the myriad unnamed lives that have shaped, and been shaped by, the city's history. This work, in capturing the ephemeral messages of appeal, underscores the act of witnessing as both a communal and a deeply personal endeavour, echoing Sharpe's assertion that "the wake" is a shared space of mourning and memory.

With Gaufi and Kgakala (2023), Lerato Shadi’s large raw linen canvases marked in red with a flow of thoughts, embody the temporal and tactile dimensions of memory. Each stroke and word inscribed upon the canvases speaks to the personal and collective narratives of the Diaspora, narratives that, as bell hooks reminds us, are deeply intertwined with the politics of recognition and belonging. Shadi's work, in its raw and evocative form, invites us to imagine the possibilities of healing and connection through the act of bearing witness to our own stories and those of others.

Helena Uambembe's installation, Booming in Statis (2023), offers a counterpoint to the themes of movement and change. Here, stasis is not synonymous with silence or absence but is instead a resonant space filled with the echoes of past struggles and triumphs. This work embodies Akwaeke Emezi's reflections on the self as a site of constant becoming, where identity is neither fixed nor singular but is instead an ongoing negotiation with the past and the present. "I am, always, a multitude of multitudes," Emezi writes, inviting us to consider the ways in which our identities are shaped by the histories we carry and the futures we imagine.

Reflecting on Naomi Di Meo's elegy to her younger self, the exhibition invites a similar introspection from its viewers. Di Meo's elegiac prose, a tender reflection on growth, loss, and the passage of time, mirrors the exhibition's engagement with the notion of bearing witness not only to the external world but also to the landscapes within ourselves. It is a reminder that mourning and memory are not merely about looking backward but are also acts of self-compassion and recognition, a way of honouring the journey of becoming.

In the subtle interplay of light and shadow, "Notes on the Wake: Rhapsody and Lamentations in Three Acts" weaves a tapestry of loss and love, a collective and individual elegy to the Diasporic experience. Through the works of Asemota, Shadi, and Uambembe, and the reflective words of Sharpe, hooks, Emezi, and Di Meo, the exhibition stands as a testament to the power of holding space for mourning, for memory, and for the myriad ways we keep watch over the echoes of our shared and singular histories. In this space, time is embodied not as a linear progression but as a rich palimpsest, a living archive of what has been, what is, and what might yet be.

there was a girl i once knew

By Naomi Kelechi Di Meo

I always mourned for my younger self. I mourned the way she walked, and spoke about the things she liked. I mourned how she was already pretty rebellious on wanting to choose her clothes for elementary school, never giving her mother the chance to prep her outfits.

I mourned how she looked at herself in the mirror without feeling like an empty plastic bag floating on the streets abandoned and forgotten by its previous owner. I mourned

how she belonged to nobody but herself. I never understood why I felt that way about my childhood self until I learned what men can do to women regardless of their age.

I mourned for the innocence that was stolen from me, piece by piece, by the lingering gazes and the whispered words that sliced through my soul like a knife. I mourned for the days when I could walk with my head held high, unencumbered by the weight of sexualization and the power it held on my body.

I grew up feeling like an outsider in my own skin, as if my Blackness was a costume I couldn't remove, a label that allowed and justified men to consume me with no hesitation. It was as though parts of my body ceased to belong to me, becoming public property for others to dissect and scrutinise at their leisure. Every glance felt like a violation, every word a reminder of my perceived otherness. I longed to reclaim the autonomy that was stripped away from me, to feel whole again in a world that seemed determined to turn me into a ghost within my own skin.

But no matter how hard I tried to bury my true self beneath layers of conformity, the echoes of my lost identity lingered, a constant reminder of the girl I once was and the woman I could have become.

As I reflect on my youth, I realise that my mourning extends beyond the loss of innocence; it encompasses the erosion of my self-worth and the gradual descent into self-loathing. It began with the insidious ways in which men would leer at me, their eyes stripping away layers of my humanity until all that remained was a vessel for their desires.

I was barely a child when I first felt the weight of their gaze, when innocence was replaced with a suffocating sense of shame. Their words, laden with suggestive undertones, twisted my perception of myself, transforming me from a carefree girl into a prisoner of my own body and their own fantasies. With each passing year, the scrutiny intensified, as if my worth could be measured by the curves of my hips or the fullness of my lips.

I learned to shrink myself, to hide beneath oversized clothes and averted eyes, desperate to escape the constant barrage of objectification. I was barely 7, I never thought i would compare myself to the toys i used to play with.

But no matter how hard I tried to shield myself from their eyes and hands, it followed me like a shadow, infiltrating every aspect of my existence. I became hyper-aware of my body, dissecting it piece by piece in a futile attempt to reclaim ownership over what had been taken from me.

The loss of innocence was not a singular event but a slow, agonising process, punctuated by moments of profound despair and resignation. I watched as my peers blossomed into confident young women, while I remained trapped in a perpetual state of self-loathing, unable to recognize what I was becoming.

The feeling of grief I carry is not just for the loss of innocence; it's a mourning for the shattered pieces of myself scattered along the path of my existence. It's a sorrow that seeps into the very core of my being, leaving me adrift in a sea of uncertainty, unsure if what I am now remotely resembles what I once was.

The lines between who I am and who I am expected to be blur until they are indistinguishable, leaving me feeling like a stranger in my own skin.

Even though I have grown to accept the body I call my home, I cannot help but feel a pang of sorrow for the girl I once was and the woman she could have become. Despite the strides I have made in reclaiming my identity and rebuilding myself from the graveyard they made of me, the grief for what was lost still lingers, a silent companion in my journey through life.

For even as I embrace the woman I have become—resilient and patient—I cannot shake the feeling that somewhere along the way, a part of me was left behind, buried beneath the weight of being Black and a woman.

I mourn for the dreams that were shattered, for the opportunities that were denied, and for the innocence that was stolen from me before I had the chance to truly see it bloom.

I never thought it was possible to miss a version of oneself that I barely remember and no longer exists. I just hope I can spot her in my reflection one day.

Biographies

Leo Asemota is an Edo native. He has places of residence in London and in his birthplace Benin City, Nigeria.

Lerato Shadi is an artist born in Mahikeng who currently lives and works in Berlin. She studied visual art at the University of Johannesburg and earned an MA in Spatial Strategies from Weißensee Academy of Art Berlin in 2018. She received the Alumni Dignitas Award from the University of Johannesburg in 2018 and in the same year Shadi was a fellow at Villa Romana in Florence, Italy. Her works have been shown internationally in numerous solo and group exhibition, among others in the Bundeskunsthalle, Bonn, Germany (2023), Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Germany (2022), at the Palais de la Porte Dorée and in the Musée d’art moderne both in Paris, France (2021); in solo shows at KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlin and at Kunstverein in Hamburg, Germany (2020); during the 14th Curitiba Biennial in Brazil and at SAVVY Contemporary, Berlin, Germany (2019); Kunsthal Amersfoort,Holland, Zeitz Museum of Contemporary Art Africa in Cape Town, South Africa (2018). Her video work Mabogo Dinku was part of the Artists’ Film International programme 2020, organised by Whitechapel Gallery London, and presented in art institutions around the globe. In spring 2022, her monograph was published with Archive Books, Berlin.

Helena Uambembe is an Angolan-South African artist whose work interrogates the dyadic relationship between the political (world politics) and the domestic (personal politics). Drawing from personal and familial history, Uambembe maps the ideological and intimate space created by the historical and colonial links between Angolan, Southern African and global history. This complex family history (itself a disruption of current accepted narratives of post-colonial Africa), the 32 Battalion, Pomfret and her Angolan heritage are dominant themes in her multidisciplinary approach. In 2022 Uambembe was awarded the Baloise Art Prize 2022 for her installation What you see is not what you remember, shown at Art Basel, Statements Section. She is currently based in Berlin where she is a fellow of the Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD).

—-

Villa Romana was founded in 1905 by an artist for artists,as a space in which to experiment, breathe, and live in togetherness. A place where co-habitation could become an opportunity for individual artistic engagement and communal change.

Villa Romana is not a villa, it is not a museum, but a house. It is not an arcadia but a real place, with its challenges and its cracks; a physical and mental space where to feel safe and at times unsettled, as in life. This is the fundamental and grounding deliberation at the core of the newly started phase of this institution in becoming.

Since 2023 Villa Romana has been transforming into A House for Mending, Troubling, Repairing, unfolding a new vision and programme for the historical artist residency and artists’ house founded nearly 120 years ago by Max Klinger. Nourishing a hospitable and critical laboratory for artists, activists, cultural workers, diasporic communities, children, animals and plants; the programme envisions an agenda and climate that grapples with the very core of the institution Villa Romana: its infrastructure, domestics, community, locality, and garden. To see the Villa as a home for crafting the tools and practices to face times that ask of us a radical and planetary repair of an asymmetric world.

The times of crisis in which we live force us to rethink the way in which we co-inhabit the planet, and to reconsider some of the founding values of Western culture - a culture that has discovered itself to be ecocidal, and epistemicidal towards systems of knowledge other than the grand Eurocentric narrative. In order to imagine an ecologically and socially sustainable future, Villa Romana opens itself as a laboratory for critical reflection and confrontation, as a space for socio-artistic-cultural experimentation, and at the same time as a workshop and home for developing tools and practices that enable us to tackle the difficult work of repair to which we are called. We propose a programme that embraces a path of institutional self-reflection and infrastructural transformation. One that starts from the practice of co-habitation and is characterised by doing together, by ecological thinking, and by anti-racist and anti-discriminatory acting, to elaborate practices of radical conviviality, inclusion, sharing and restitution.

Credits

Curator: Mistura Allison

Director: Elena Agudio

Administration: Claudia Fromm

Production Exhibition: Giulia Del Piero

Production House: Ala Turcan, Victor Cebotaru

Assistance: Maike Wild

Food Rituals: Kaaj Tshikalandand

|

|

|

|

|

|